What’s the OMB?

This is how the Ontario Municipal Board is grandly described in legal terms:

The Board can order and require or forbid, forthwith or within any specified time and in any manner prescribed by the Board, the doing of any act, matter or thing or the omission or abstention from doing or continuance of any act, matter or thing, which any person, firm, company, corporation or municipality is or may be required to do or omit to be done or to abstain from doing or continuing under this or any other general or special Act, or under any order of the Board or any regulation, rule, by-law or direction made or given under any such Act or order or under any agreement entered into by such person, firm, company, corporation or municipality.

This is how many of the people who appear before the Board describe it: #%$<&!

The Ontario Municipal Board (OMB) is a body of professionals, often lawyers or former planners, appointed by the province, who sit in panels like a court. It was established so that cities and towns who behaved erratically or ignored some greater public good could be overruled. In principle, not a bad idea. So the OMB can overrule the wishes and decisions of local governments. In principle, not a good idea.

The trouble is trying to decide what constitutes the public good. Is a garbage dump a good idea? Are corridors of hydro pylons a good idea? Are new condos close together on previously vacant land a good idea?

Cities themselves don’t have the last word. The provincial government controls Ontario cities in many ways, including how taxes are levied, and the way cities are allowed to regulate development. “Cities are creatures of the province,” as the saying goes. They are not independent.

But this could change, a bit. Four years ago a provincial law called The City of Toronto Act gave the city a way to avoid the OMB in many decisions about who builds what in Toronto. All the city has to do is set up its own municipal appeal process. But the city has failed to do this.

What’s the Official Plan?

Toronto’s Official Plan outlines what the city wants to be built, and where. It is a big document of 143 pages that sets out general principles. Finer details are covered in “secondary” plans that sometimes exist for particular areas, and in various zoning bylaws.

The Official Plan is like a constitution.

It requires interpretation. It is packed with good ideas but short on details. Figuring out those details leads to arguments and negotiations among builders and city planners and neighbours.

The Official Plan says nothing about how buildings and the space around them should look, only what they should do. The Official Plan says that some areas of Toronto are designated for “mixed use.” In other words, residential, commercial and institutional uses can be mixed together (in older planning schemes they were usually segregated).

In the fine print, Toronto’s Official Plan for mixed use areas wants to:

- create a balance of high quality commercial, residential, institutional and open space uses that reduces automobile dependency

- provide for new jobs and homes for Toronto’s growing population on underutilized lands

- locate and mass new buildings to provide a transition between areas of different scales and to minimize shadow impacts

- provide an attractive, comfortable and safe pedestrian environment

- take advantage of nearby transit services and provide adequate parking for residents and visitors

- provide indoor and outdoor recreation space for building residents in every big residential development.

Who could argue with any of that? Well, as it turns out, almost everybody.

Big buildings

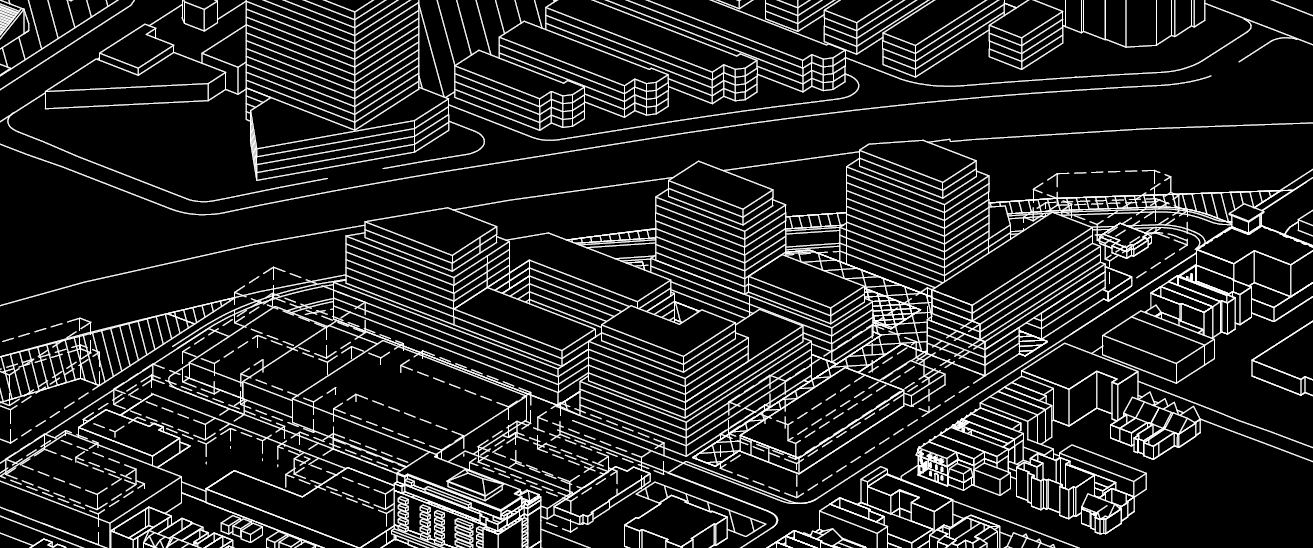

A big, tall building is being proposed near where you live. Maybe it’s a condo, maybe it’s an office building. In any case it’s really big – and according to the pictures you’ve seen, it’s really ugly.

You and your friends think it will ruin the neighbourhood.

This happens all the time. Often people live where they do because they like how the neighbourhood looks and how it functions. Large-scale change is a menace. But cities are never static. Managing a city’s progress gracefully is the tricky part.

In general along wide Toronto streets with good public transportation, big buildings are encouraged. Along side streets they aren’t.

Downtown intensification — which means filling in vacant spaces with appropriate buildings — is encouraged. Overdevelopment — whatever that means — isn’t.

The city has a million rules about building heights and how much of a site must be left open; how much parking is required; how much a building can cast shadows on adjacent buildings and sidewalks; whether a green roof is required; whether changing a site from a commercial use that employs people to a residential site that doesn’t is allowed, etc. It is a big list.

Two general approaches are evident in Toronto. In the first and more usual, a developer negotiates with city planning staff to get more or less what he wants, then the proposal is presented to the neighbours, who hate the idea. A fight often ensues, City Council gets involved, and at great emotional and financial cost the issue is settled by the Ontario Municipal Board.

The second approach is different: the developer and the neighbours are brought together by the ward councilor and ideas are exchanged. The process is usually both civil and rocky, but by the time the planning department gets involved with the technical details, World War Three has been avoided, and there’s no fight looming at the OMB.

Give and Take

In Toronto no significant building in living memory has been built entirely in accordance with the zoning or planning bylaws.

In fact, believe it or not, there’s an official procedure for circumventing those city laws. Thus builders can appeal to the Committee of Adjustment — a panel of five private citizens appointed by the city — for minor “variances” in the bylaws. And for a major variance, for example a 42-storey building where only a 6-storey building is allowed, a builder can appeal to a Community Council consisting of all the elected councilors in one of the four administrative districts of Toronto.

A crucial part of the process is for major developers to offer the city a “public benefit” in exchange for loosening the bylaws.

This give-and-take, which on the surface looks rather like a bribe, is specifically allowed under Section 37 of the Planning Act (that’s why it’s called a Section 37 benefit). Section 37 benefits are rather awkward because the city can’t ask specifically for what it wants. That would be the equivalent of imposing a tax, which the city isn’t allowed to levy. Instead a game of cat and mouse takes place.

It’s done differently elsewhere. In New York, planning codes are very detailed (there are 41 different types of commercial district), and about 90% of new buildings adhere to the codes without appeals or horse-trading. In London, England, you can make a 12% profit on a real estate development, but anything over that comes back to the city in the form of subsidized housing and other public amenities paid for by the developer. Vancouver charges a set fee which goes into specific public benefits in the area of the development. Depending on the area, the fee for a new development can be as much as $168 per square meter of floor area.