Essay by Max Allen, curator, Urbanspace Gallery

One of the meanings of the word hylozoic is “almost alive.” So what could it mean for buildings or groups of buildings to be almost alive?

It sounds like science fiction, but you can see it happening on the streets of Toronto and in cities worldwide: People and technologies are merging.

What will cities, and the buildings within them, look like as this proceeds?

The other day I was standing next to a fellow at the corner of Richmond and Peter, waiting for the traffic light to change. He was busy with his Blackberry, hardly aware of the city around him. His body was present, here, now, but his attention wasn’t. As we walked up Peter, I came up right alongside him and snooped over his shoulder at what he was doing. Little words on a screen. When he finally noticed me, he jerked up in surprise, scowled, and went back to his screen. At Queen and Peter, he went east along Queen and I went north toward Grange Park.

A few minutes later there he was again, headed up John Street toward the park, still buried in the virtual world of his Blackberry, the physical world invisible to him and immaterial (in both senses).

I wondered: If people aren’t really here, what do they need cities for? And meanwhile what are cities and buildings doing?

Quite as lot, as it turns out. Responsive buildings and public spaces (automated traffic control systems outdoors; air flow, temperature, lighting and elevating systems indoors) have evolved to become more and more aware of our activities at the same time that individuals are merging with machinery – pacemakers, cell phones, iPods, Blackberries. This evolution is no accident. Humankind is planning it, designing it, and taking advantage of it.

Philip Beesley, with his experimental structures, imagines that buildings and the cities they inhabit will soon be noticing us more and more. Using cybernetic feedback loops they will build and rebuild themselves by extracting usable materials, mostly waste materials, as “food” from the air and water – and will react to the presence of people even more than they do today. Empathetically, Beesley suggests. Almost as if they were alive.

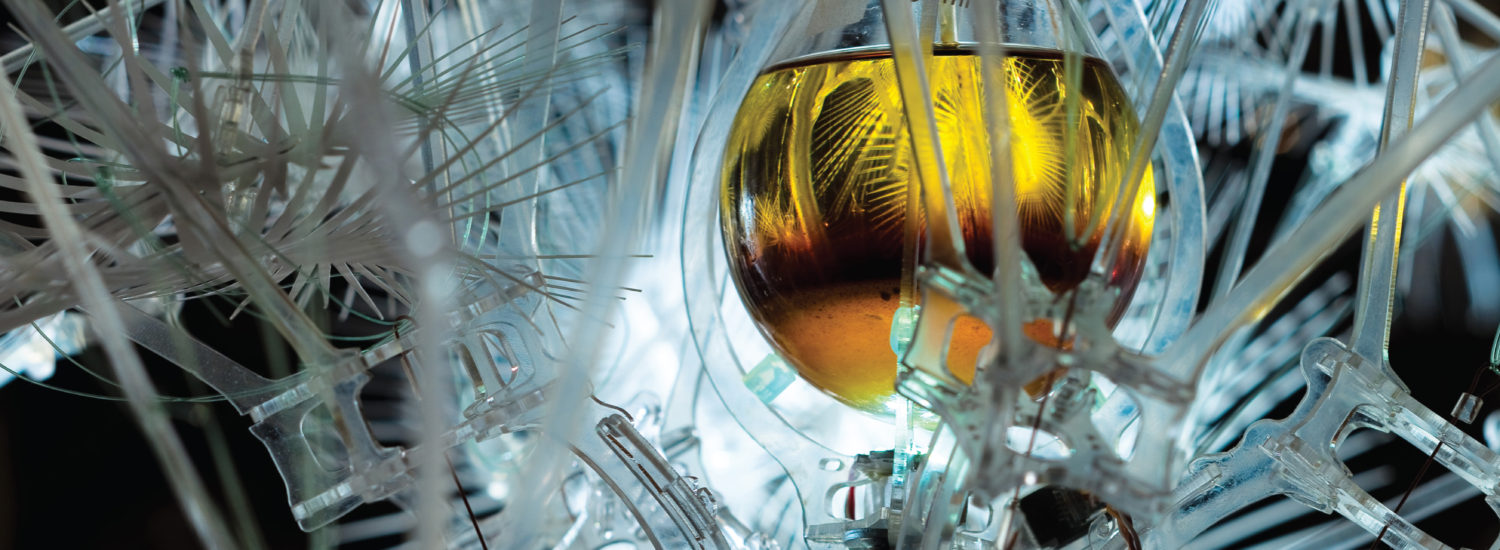

The Canadian pavilion by Philip Beesley at the 2010 Venice Biennale of Architecture

Hylozoic is a Greek word that means almost alive.

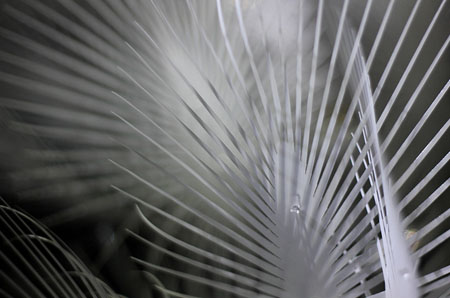

“Hylozoic Ground is an elaborate sculptural environment, a wilderness of layered acrylic components embedded with technologies and lights, inviting exploration. As you approach, proximity sensors detect movement and respond with caressing and swallowing motions, sending out an invitation to engage.

“Sensors in the tips of appendages react to human touch by setting off an array of microprocessors, producing choreographed movements that ripple through the structure. Stray organic matter from visitors is drawn up by the breathing apparatus’s peristaltic motion and absorbed in the upper-layer filters.

“With each new version, the project has taken a step toward becoming a more complete artificial organism. The design of the components that support the kinetics has continued to evolve – as have the software and hardware behind the responsive movement, which were developed by mechatronics expert Rob Gorbet, a fellow professor with Philip Beesley at the University of Waterloo.

“Dr. Rachel Armstrong, a London-based medical doctor turned artificial life researcher, collaborated with Beesley on the lymphatic system. A network of flexible tubing connects to a series of flasks containing mixtures of oils, Venice canal water and minerals, approximating the conditions for simple cell evolution. This self-renewing chemical system explores how parts of a building might work like a metabolism to transform noxious materials in the environment into benign ones.

“Dr. Armstrong imagines that visitors entering the Venice pavilion will feel as if they are being embraced by a quivering membrane that licks and sniffs at them in an experience “rather like being greeted by an expansive, surreal dog that is pleased to meet you.”

From an article by Terri Peters in the September issue of AZURE magazine.